The other day I had an experience in the operating room that I want to talk about. It helped remind me, in a very dramatic way, how nothing that we do is “routine” in the way most people understand the term.

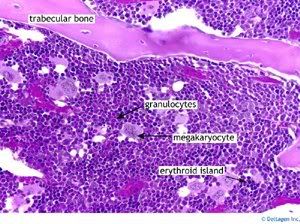

One of my roles in our department is to be a member of the bone marrow transplant team. In that capacity, I am called upon to harvest bone marrow from healthy people who have agreed to donate, usually to a relative. Since I am a pediatrician, both donors and recipients are often children, and they are usually siblings. This puts parents in an awkward position because they have to subject one child (the donor) to some degree of risk in order to maximize the chance of another child (the recipient) surviving their cancer. The ethics of a child putting him/herself at risk to donate marrow is a very interesting topic, and I hope to discuss that in more depth in a future blog post.

How much risk is involved? Not that much. In the years I have been participating in bone marrow harvests, first as a resident, then as a fellow, and now as the “surgeon of record,” I have seen fewer than half a dozen donors have complications significant enough to require overnight hospitalization. The vast majority of donors go home an hour after the procedure is completed, suffering nothing worse than sore hips and mild anemia.

This week, things threatened to turn out very differently.

The donor was an 8 year old girl who was giving bone marrow for transplantation into her 13 year old brother, who has acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Bone marrow transplantation (BMT) for AML is routine in the United States when there is an appropriate family member donor, and BMT clearly improves survival of children with AML. I met the donor, her father, and her aunt in clinic the day before the harvest to answer their questions. As expected, one question involved how risky the procedure is for the donor. I answered that the procedure is actually quite routine at our hospital, and in more than a decade, I have seen only 3 or 4 kids who were bone marrow donors require hospitalization to treat a complication of the donation, and never for more than a night. This reassured the father tremendously.

The next day, things started out in the operating room quite uneventfully. The patient came in with her mother, went to sleep, and her mother kissed her goodbye and left. We started the procedure, but part way through the patient required a bit more anesthesia. About 30 seconds after the anesthesia level was increased, the anesthesiologist noticed a sharp decrease in the patient’s blood pressure, and moments later could not feel a pulse in her neck. We abruptly stopped the harvest and called for help. As 5 additional anesthesiologists and nurses descended on our room, we turned down the anesthesia, flipped the patient over onto her back, and began chest compressions. Thankfully, within just a few seconds we could feel a pulse again, her blood pressure started to rise, and the crisis ended as abruptly as it had begun.

Next came an obvious question: do we continue? After all, the donor just had a life threatening event… what if it happened again? Was it worth risking her life for this procedure? Surprisingly, the answer to that question was easy. We had to continue, because her brother (the recipient) had already received what would otherwise be lethal doses of chemotherapy, and would surely die without getting bone marrow from her. So, with a choice of risk to one patient versus certain death of the other, the choice was easy. After a break to ensure that the donor was doing well and able to continue safely, we resumed our harvest.

This story, unlike some I have shared, has a happy ending. The rest of the harvest went smoothly, we got the marrow her brother needed, and everyone is currently doing great. The donor did stay overnight in the hospital, but she went home the next morning after observation and a blood transfusion, and she continues to do well. Her brother tolerated the marrow infusion without difficulty, and continues on his own road to recovery.

Despite the happy ending, this incident really shook us up. Was I rash to downplay the risks to the donor in discussing the procedure with the family? Are there any circumstances that would have justified stopping in the middle? What would the consequences have been if the donor had NOT done well after we resumed the harvest? How would her brother feel if his sister had passed away during this potentially life saving procedure for him? We (the BMT team) talked about these issues at length in the evening after the harvest. I think it’s fair to say that the experience has changed no one’s mind about the importance of bone marrow donation, and no one feels that anyone did anything wrong.

But it has changed one thing: I sure will be a lot less blithe in my reassurances in the future. Sure, the procedure is routine. Of course, I still haven’t seen anyone suffer a complication of donation that required more than an overnight stay in the hospital. But things certainly could have turned out very differently. I will absolutely remember that routine does NOT mean risk-free.

7 comments:

Is there some way to determine that the girl might have had a predisposition to this event? Perhaps an "allergy" to the anesthesia?

Would it be important to have the girl followed up?

It's almost impossible to predict reactions like this. However, her parents asked afterwards if they should alert the anesthesiologist the next time she needs surgery for anything, and I think THAT would be an excellent idea, because she may have problems in the future (though this could very well have been a one time thing).

Regarding follow-up, we watched her in the hospital overnight and have seen her back in clinic since then (and of course, we see her most days when she's in visiting her brother).

Your story is just one in a list of things that has made me really think about "Informed Consent" lately, both as a patient and as a doctor. I'll be blogging about it soon. I'd love to link to your story or your thoughts on the topic. Thanks,

Lisa, Feel free to link to the story. Informed consent is a topic I've also thought about blogging about. I also have experience as a patient (though not as a cancer patient), so I've experienced the consent process from both sides as well. Would be great to talk more about this (or to both blog about it and compare thoughts that way).

doctor david,

God Bless you for your hindsight. It's always difficult to predict an individual's response to anything. I have had patients react violently to the most simple medications. You can't know everything. In this instance, though the procedure IS routine, so it might be best to always alert patients and families to the very real dangers of anesthesia. I have found this helps enormously. I think most people know that any surgery is a risk, and it never hurts to remind that these procedures require a deep level of sedation and life support. I'm of course, glad that all is well. It is the rare, yet possible complications of surgery, trauma and invasive procedures that scare me the most, as well as the side effects of even minimally invasive procedures (and medications). When a patient does well you're likely to hear, "Thank God", but when things go awry.." its' blame the doctor or nurse".

Well hehe actually it's very boring actually many times, but I became a doctor because you earn good money and I don't really care about people, I just care about the truth, I guess have that you seem dr house sometime ojn tv, something like that, it's interesting that someone like me, like him exist ahaha

I became Doctor to touch boobs for free, I was wrong :P ... anyway nice post.

Post a Comment